English Fashion 1813 English Fashion 1750

In the 1780s the styles from the previous decade continued to exist popularized, emphasizing more casual clothing in both womenswear and menswear. At the same fourth dimension, mode publications were becoming a vital function of spreading trends and mode news.

The informal styles for men and women that were introduced in the previous decade were firmly entrenched by 1780s. For the old, the frock coat with a high turned-downwardly collar and wide lapels, hip-length sleeveless waistcoat, and breeches that outlined the shape of the thighs dominated men's daytime wardrobes. For the latter, in addition to the robe à l'anglaise, robe à la polonaise, robe à la lévite, robe à la circassienne, and caraco-and-petticoat combination that gained popularity in the 1770s, the robe à la turque, the redingote (the Gallicization of "riding coat"), and the chemise were new options for daywear. A more than regular fashion press that emerged in the 1770s continued to expand, disseminating new styles more quickly to a wider audience.

Womenswear

Afunction from the chemise, the various styles referred to above were open robes worn over matching or contrasting petticoats and characterized by a fitted bodice that airtight at the center front, commonly with hooks and eyes or curtained lacing (Figs. 1-5). The shaped pattern pieces were sometimes lightly boned at the center forepart and center dorsum seams, ensuring a smoothen line (Figs. 1-3, v). In the preceding decade, the centre dorsum panels of the robe à fifty'anglaise were stitched downward as far as the waist and released below to create the fashionable fullness of the skirt (see 1770-1779 overview); in the 1780s, the tightly pleated skirt was cut separately from the bodice, which ended in a pronounced 5 at the center back waist, accentuating the curve of the lower spine (Figs. 1, 2, 4, 5, half dozen). As in the 1770s, the preferred fabrics for women'south daytime garments were plain or minimally patterned lightweight silks—stripes of even width were especially in vogue—and cottons that were more suitable to gowns with close-plumbing equipment bodices and finely pleated skirts (Figs. 1-six).

In Adelaïde Labille-Guiard's monumental Self-Portrait with Ii Pupils, Mademoiselle Gabrielle Capet and Mademoiselle Carreaux de Rosemonde (Fig. seven), exhibited at the Salon of 1785, the artist, who two years earlier was one of the few women to be admitted to the Académie Royale de peinture et de sculpture,

"presented herself to a large and diverse Parisian audience equally a protean figure, not simply as an ambitious portraitist but as well in the guise of a stylish sitter." (Auricchio 45)

Seated at her easel, brushes in hand, Labille-Guiard wears a luminous stake blue satin robe à l'anglaise, lined in white silk, with a matching petticoat with one visible seam along her left leg. Ruffles of fragile floral-and-foliate patterned lace and white silk bows decorate the low wide neckline typical of the 1780s and the cuffs of her tight-fitting, elbow-length sleeves. Backside her, Mademoiselle Capet also wears a robe à l'anglaise of soft brownish silk taffeta accessorized with a sheer white bonnet, fichu, and sleeve ruffles with matching silk ribbons, while Mademoiselle Carreaux de Rosemonde has sensibly covered her clothes with a white linen or cotton smock to protect it from her oil paints.

In her reading of this painting, art historian Laura Auricchio draws attention to Labille-Guiard's skill at depicting "a boundless assortment of materials" including "the shine of satin, the intricacy of lace, the delicacy of feathers… the deep shadows of plush velvet… the porcelain texture of flawless skin" and the "cornucopia of visual treats," including Labille-Guiard herself in her stylish and highly impractical dress (50). The artist's flirtatious presentation of her "elaborately clothed but voluptuously revealed body" is closely allied to "another form of commercial imagery associated with women—the mode plate" (51). Auricchio suggests that two 1784 plates from the Galerie des Modes (Fig. 8) may have provided inspiration for the creative person (51). Labille-Guiard thus "simultaneously demonstrated that she possessed the skills required of a portraitist… [and] declared an affinity with the world of trade that was forbidden to academicians and to well-bred women alike" (Auricchio 51).

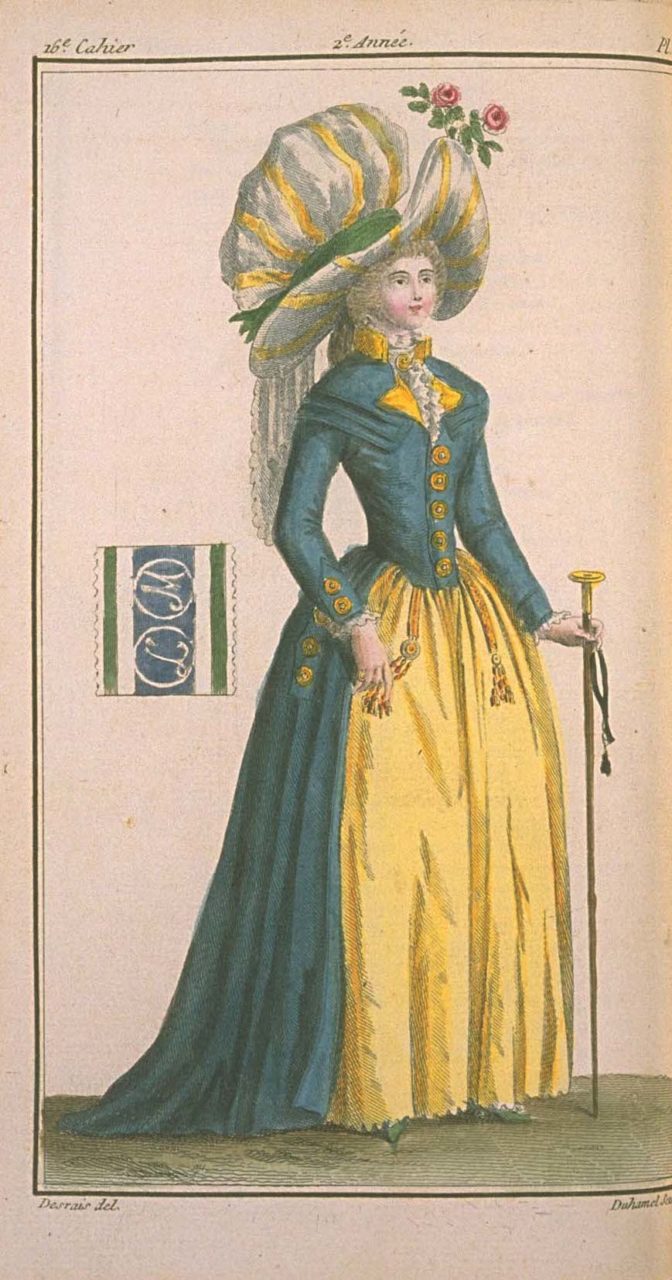

Fig. 1 - Nicolas Dupin (French). Page from Gallerie des modes, 1778-1785. Engraving; 23 x sixteen cm. Paris: National Library of France. Source: BnF Gallica

Fig. 2 - Designer unknown (French). Robe à l'Anglaise, ca. 1785-87. Silk. New York: The Metopolitan Museum of Art, C.I.66.39a, b. Buy, Irene Lewisohn Heritance, 1966. Source: The Met

Fig. 3 - Designer unknown (French). Robe à 50'Anglaise (detail), ca. 1785-87. Silk. New York: The Metopolitan Museum of Art, C.I.66.39a, b. Purchase, Irene Lewisohn Bequest, 1966. Source: The Met

Fig. 4 - Creative person unknown (French). Robe à la Turque, Nov ane, 1786. Engraving. Tokyo: Bunka Gauken University Library, SB00002310. Source: Bunka Gauken

Fig. v - Joshua Reynolds (British, 1723-1792). Selina, Lady Skipwith, 1787. Oil on sail; 128.three ten 102.two cm. New York: The Frick Drove, 1906.1.102. Henry Clay Frick Bequest. Source: The Frick

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown (British). Gown, ca. 1780. Cotton, resist- and mordant-dyed, block-printed, painted and lined. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.217-1992. Source: V&A

Fig. 7 - Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (French, 1749-1803). Self-Portrait with Two Pupils, Marie Gabrielle Capet (1761–1818) and Marie Marguerite Carreaux de Rosemond (died 1788), 1785. Oil on canvas; 210.8 ten 151.one cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 53.225.5. Gift of Julia A. Berwind, 1953. Source: The Met

Fig. viii - Nicolas Dupin (French). Plate from the Galerie des Modes, 1778-1785. Engraving; 23 x 16 cm. Paris: National Library of French republic. Source: BnF Gallica

Fig. 9 - Artist unknown (French). Redingote Magasin des modes nouvelles, April 20 1787. Engraving. Tokyo: Bunka Gakuen Library, 070379307. Source: Bunka Gakuen

Although women had worn masculine-inspired wool riding habits throughout the eighteenth century, in the 1780s the redingote constituted fashionable day attire (Fig. 9). This coat dress was also based on menswear with a high collar, wide lapels, and double-breasted closure with outsized buttons, and was often accessorized with paired watch fobs (Fig. 9)—some other nod to a electric current fad among stylish young men. Few redingotes have survived, but their popularity in this decade is evident in the pages of the Galerie des Modes (1778-1787) and the Cabinet des Modes that began publication in 1785 and changed names twice before ceasing in 1793. In November 1786, the retitled Magasin des Modes Nouvelles françaises et anglaises illustrated a immature adult female in a redingote of "lemon-xanthous wool, with apple-light-green stripes" with a collar and lapels à la marinière (sailor) and a double-tiered "ample gauze fichu" with its ends knotted "en cravatte" (Fig. 10). Barely visible under the hem of her mannish garment are her highly feminine shoes of pink satin trimmed with a black silk ribbon (Fig. 10). At the cease of the ii-page description that provides further details of her ensemble, "frizzed" crew, and "chapeau-bonnette…très bouffante," the editor notes that "our Ladies have adopted the mode of redingotes" from English women. In spite of the flamboyantly trimmed hats and delicate footwear that generally accompanied the redingote, its visual similarity to men'southward dress prompted the same critiques that were leveled at women throughout the century for transgressing gender boundaries by their adoption of tailored riding suits. In 1789, The Lady'south Magazine worried that,

"[O]f late, I recall, women appear, in their great coats, neckcloths, and one-half-boots, with then masculine an air, that if their features are not very feminine indeed, they may easily be mistaken for young fellows; specially when a watch is suspended on each side of a petticoat." (Waugh/Women 127) (Fig. 9)

While wool redingotes were well-nigh closely associated with men's fashionable daywear, they were likewise made of silk. A watercolor cartoon of Marie Antoinette dating to virtually 1780 (Fig. 11) shows the queen in an ivory redingote (likely silk) with a black neckband and zigzag trimming and narrow bands of fur edging the skirt fronts and petticoat hem. An extant example in the collection of Palais Galliera (Fig. 12) with an impressive scalloped double collar is of yellowish silk taffeta. In her portrait by Labille-Guiard, the Comtesse de Selve (Fig. 13) wears a chic double-breasted night greyness velvet redingote with gold string crisscrossed around the buttons like to the plate in the Magasin des Modes nouvelles and a matching hat with a single white plume.

Fig. x - Duhamel (French). Cabinet des modes, ca. 1778-1785. Engraving; 23 ten sixteen cm. Paris: National Library of France. Source: BnF Gallica

Fig. 11 - Artist unknown (French). Marie Antionette in a Redingote, ca. 1780. Engraving. New York: BGC Visual Media Resource Collection, 214248. Source: Fashion Muse

Fig. 12 - Designer unknown (French). Redingote and Skirt, ca. 1780-1785. Tafetta, silk. Paris: Palais Galliera, 1988.121.4ab. Source: Dreamstress

Fig. 13 - Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (French, c. 1749-1803). Comtesse Charlotte Elisabeth de Selve (1736-1794), 1787. Oil on sail. Source: Wiki

The clothes that would proceeds particular prominence in the 1780s and the following decade was the white muslin chemise, or chemise à la reine (Fig. xiv). Although Marie Antoinette was vilified in 1784 for allowing herself to be portrayed in this jumpsuit gown (Fig. 15) adorned only with a matching double-ruffled collar, shallow cuffs, and a sheer, gilt-colored sash, the chemise was worn by many women across the socio-economic spectrum and "the evolution of this pivotal garment illuminates a period of profound change in French way and social club" (Chrisman-Campbell 172; meet also 172-199). As wearing apparel historian Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell points out, although "the chemise à la reine was similar to the female undergarment in construction… it was not identical [and] information technology diameter a closer resemblance to the unstructured white gowns traditionally worn past young children of both sexes" (Chrisman-Campbell 172). Different the two-piece styles described above, the chemise was put on over the caput and did not crave a pannier and, while muslin was a favorite choice for this dress, "crêpe, silk gauze, backyard, and linen were also used" (Figs. 14, 15) with some of these lightweight fabrics being washable (Chrisman-Campbell 174-175). Sold by couturières and marchandes de modes, the chemise's

"combination of practicality and novelty made [it] an essential function of the fashionable female person wardrobe fifty-fifty before it received Marie-Antoinette's endorsement and the soubriquet 'à la reine.'" (Chrisman-Campbell 172, 176)

In its early on iteration, the chemise was loose-plumbing equipment, with the excess fabric gathered at the neckline and shoulder seams and controlled at the waist by a wide sash, commonly of a contrasting color (Figs. 14, 15). A rare surviving example of a chemise in the collection of the Manchester Metropolis Galleries "with channels sewn into the sleeves for ribbons" is similar to those worn past Marie Antoinette and Madame Lavoisier (Fig. 16), depicted with her husband by Jacques-Louis David in 1788 (Chrisman-Campbell 193). The style of arranging the sleeves into puffs seen in both paintings was called "attachées sur les bras" (Chrisman-Campbell 193). David has meticulously recorded the sheerness of Madame Lavoisier's chemise—the nighttime wood floor and hem of her white petticoat are visible through the gown'due south transparent cotton train.

While French women eagerly adopted the robe à l'anglaise, the redingote, and other English language styles of dress and headwear, English women were quick to don the chemise (Fig. 17). An admiring husband's description of his wife's charms on an outing to Ranelagh (a popular London pleasure garden) that was published in the Lady's Magazine in 1786 might well employ to Madame Lavoisier'south ensemble:

"She had cypher on but a white muslin chemise, tied carelessly with celestial blue bows; white silk slippers and slight silk stockings, to the view of every impertinent coxcomb peeping under her petticoat. Her hair hung in ringlets down to the bottom of her back…" (quoted in Cunnington/Underclothes 92)

Another husband, also "cited" in the Lady'due south Magazine in the same yr that Marie Antoinette'south portrait was displayed at the Salon, was confounded by his wife'due south advent in her "new frolic" that was "like none of the gowns [she] used to clothing" and further perplexed by her explanation that she was garbed in a "chemise de la reine," since he was not a "master of French." On learning that she was, in effect, wearing "the queen's shift," he remonstrated "…what will the world come up to, when an oilman'due south wife comes down to serve in the shop, not only in her shift, simply that of a queen" (quoted in Waugh/Women 123).

Fig. 14 - Nicolas Dupin (French). Chemise à la reine, ca. 1778-1785. Engraving; 23 ten xvi cm. Paris: National Library of France. Source: BnF Gallica

Fig. 15 - Élisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun (French, c. 1755-1842). Marie-Antoinette, ca. 1783. Oil on canvas; 92.seven x 73.1 cm. Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1960.6.41. Timken Collection. Source: NGA

Fig. 16 - Jacques Louis David (French, 1748-1825). Antoine Laurent Lavoisier (1743–1794) and Marie Anne Lavoisier (Marie Anne Pierrette Paulze, 1758–1836), 1788. Oil on canvas; 259.7 x 194.6 cm. New York: The Metopolitan Museum of Fine art, 1977.10. Purchase, Mr. and Mrs. Charles Wrightsman Gift, in award of Everett Fahy, 1977. Source: The Met

The chemise popularized the vogue for white more broadly in this decade as is axiomatic in portraits and style platesshowing women in white, 2-piece cotton and silk gowns and in surviving garments (Figs. 18, nineteen). In 1786, the Comtesse de Provence, the queen'southward sister-in-police, saturday for Joseph Boze who depicted her in high-styled robe à l'anglaise and petticoat of gleaming ivory silk satin trimmed with scallop-edged lace and matching bowknots and a satin-striped fichu (Fig. xx). The post-obit year, the Magasins des Modes nouvelles illustrated a young adult female in a "fourreau" (a gown with back panels stitched from the dorsum of the neck to the hem) of white linen over a petticoat of white [silk] taffeta, and informed its readers that for morn walks, especially during fine weather, white fourreaux, robes à l'anglaise, and caracos with matching petticoats (Fig. 21) should be worn over white underpetticoats and that blue, pink, royal, and other colored underpetticoats, or "transparens," were out of style.

Fig. 17 - George Romney (English, 1734-1802). Mrs John Matthews, 1786. Oil on canvas. London: Tate Museum, N04490. Presented by Miss Winifred Bertha de La Chere in accordance with the wishes of her uncle, Henry, 1st Viscount Llandaff 1929. Source: Tate

Fig. xviii - Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (French, 1755–1842). Comtesse de la Châtre (Marie Charlotte Louise Perrette Aglaé Bontemps, 1762–1848), 1789. Oil on canvas; 114.three x 87.6 cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 54.182. Gift of Jessie Woolworth Donahue, 1954. Source: The Met

Fig. xix - Designer unknown (British). Robe à fifty'anglaise, ca. 1780. Cotton, flax. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1982.291a, b. Gifts in retentivity of Elizabeth Lawrence, 1982. Source: The Met

Fig. xx - Joseph Boze (French, 1745–1826). Marie-Joséphine-Louise de Savoie (1753–1810), comtesse de Provence, 1753. Oil on canvas; 192 10 w 134.v cm. Westerham: National Trust, Hartwell Firm, 1548062. gift to the National Trust with the house as a hotel by Richard Broyd, 2008. Source: Art UK

Fig. 21 - Designer unknown (English). Caraco and Petticoat, ca. 1789. Fine white linen, embroidered in silk. Paris: Musée de la Mode et du Costume, 1959.97.4. Source: Dreamstress

Fig. 22 - Maker unknown (French). Gazette des atours de la Reine Marie-Antoinette pour fifty'année 1782, 1782. Taffeta, silk. Paris: Archives nationales, AE/I/6 n°2. Source: ARCHIM

In the 1780s, Queen Marie Antoinette, who spent extravagantly on her wardrobe and could afford the most richly brocaded silks, purchased the newly stylish lightweight, drapey fabrics for both her informal daywear and her formal gowns. The pages of the Gazette des Atours de Marie Antoinette, an anthology containing textile swatches of gowns fabricated for the queen in 1782 (Fig. 22), are filled with taffetas (plain woven silks) in solid colors and stripes, some with ikat patterning, that were used for "Robes Turques," "Lévites," "Robes angloises," "Redingotte," "Grands habits," "Robes sur Le petit panier," and "Robes sur Le grand Panier" (James-Sarazin 41-44) (Figs. 2, 4, 12). The inscription next to a swatch of cream-colored taffeta ordered for a 1000 addiction to be worn at Easter indicates that the apparel was trimmed by "Mlle Bertin," who likely lavished yards of iii-dimensional trimmings onto this entirely apparently fabric. In 1783, Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun reprised her 1778 portrait of Marie Antoinette (much admired by the purple espoused) in which the queen wears a frothy k addiction of white silk with white-and-gold trimmings (Vigée-Lebrun updated the queen'due south coiffure in the later version) (see 1770-1779 overview) A (slightly) less formal dress (probably a robe parée) dating to the 1780s (Fig. 23) in the collection of the Royal Ontario Museum said to have been worn by Marie Antoinette is of ivory satin embroidered in silk and metal threads and sequins with ribbon swags, tassels, and delicate florals and foliage in shades of pink, green, blue, and ivory.

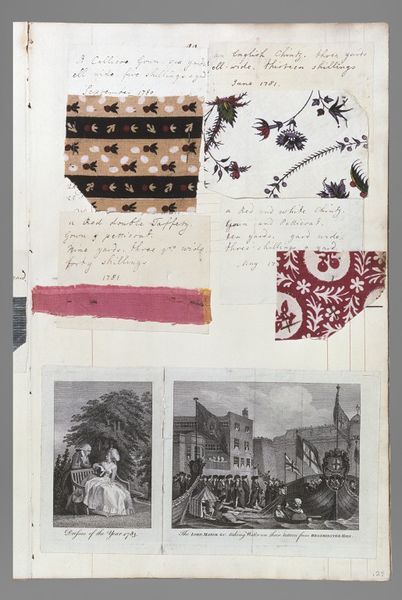

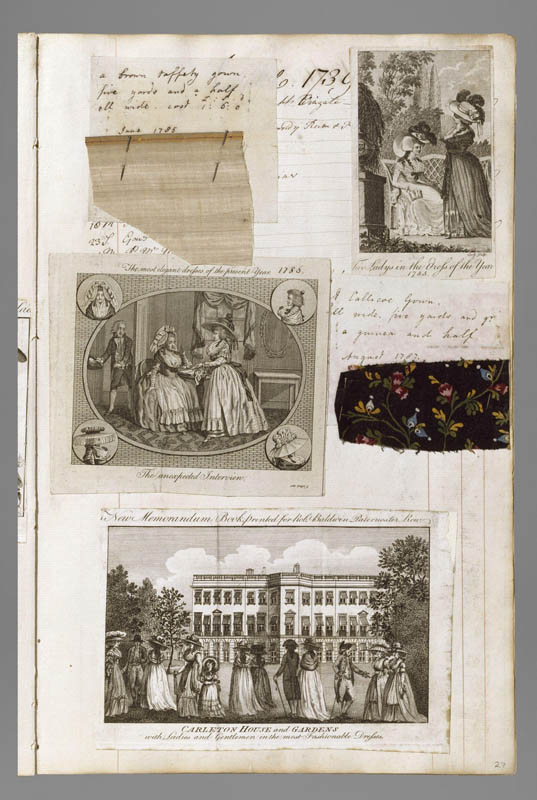

Barbara Johnson (1738-1825), girl of a clergyman from Olney, Buckinghamshire, who kept an album with fabric swatches of all her gowns (Figs. 24 & 25) commencement in 1746 at the age of 8, bought several examples of understated silks and cottons for gowns and petticoats in the 1780s. These included a "Callicoe" with black-and-tan stripes patterned with tiny sprigs in September 1780; a "Scarlet double Taffety" [plain weave] and "an English Chintz" with a blue, red, and green floral pattern on a white ground in 1781; "a strip'd Satin" in night green and dusty rose-pink in December 1782; "a chocolate-brown taffety" in June 1785; and two more "Callicoe[southward]," one with a small meandering vine pattern in blue, yellow, and light-green on a black ground in August 1787 and another with small floral-and-foliate sprigs in yellow, deep pink, white, and light brown on a blackness ground in Oct 1789 (Rothstein/Barbara Johnson'southward Album of Styles and Fabrics). While many British and French chintzes featured white or low-cal-colored grounds, dark grounds such as light-green, dark-brown, and black, known as "ramoneur" (chimney sweep) in French, were peculiarly pop in this decade and the 1790s (Fig. 25).

In add-on to domestically produced printed cottons that targeted a range of consumers, elite women favored expensive, skillfully painted-and-dyed and embroidered Indian cottons for the refinement of their embellishment and the high quality of the material itself (Figs. 26, 27).

Fig. 23 - Designer unknown (French). Marie Antionette's dress, ca. 1780s. Ivory satin with silk, metal thread, sequins. Toronto: Imperial Ontario Museum. Source: ROM

Fig. 24 - Artist unknown. Page from Barbara Johnson'southward Album of Styles and Fabrics, ca. 1780s. Paper, parchment, textiles. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.219-1973. Source: V&A

Fig. 25 - Creative person unknown. Folio from Barbara Johnson'southward Album of Styles and Fabrics, ca. 1780s. Paper, parchment, textiles. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.219-1973. Source: V&A

Fig. 26 - Designer unknown (English language). Dress (robe à l'anglaise), ca. 1780s. White cotton chintz with polychrome indian floral print; "compères" forepart with lacing; border of printed fabric at center front, hem and cuffs.. Kyoto: Kyoto Costume Found, AC6978 91-11-one. Source: KCI

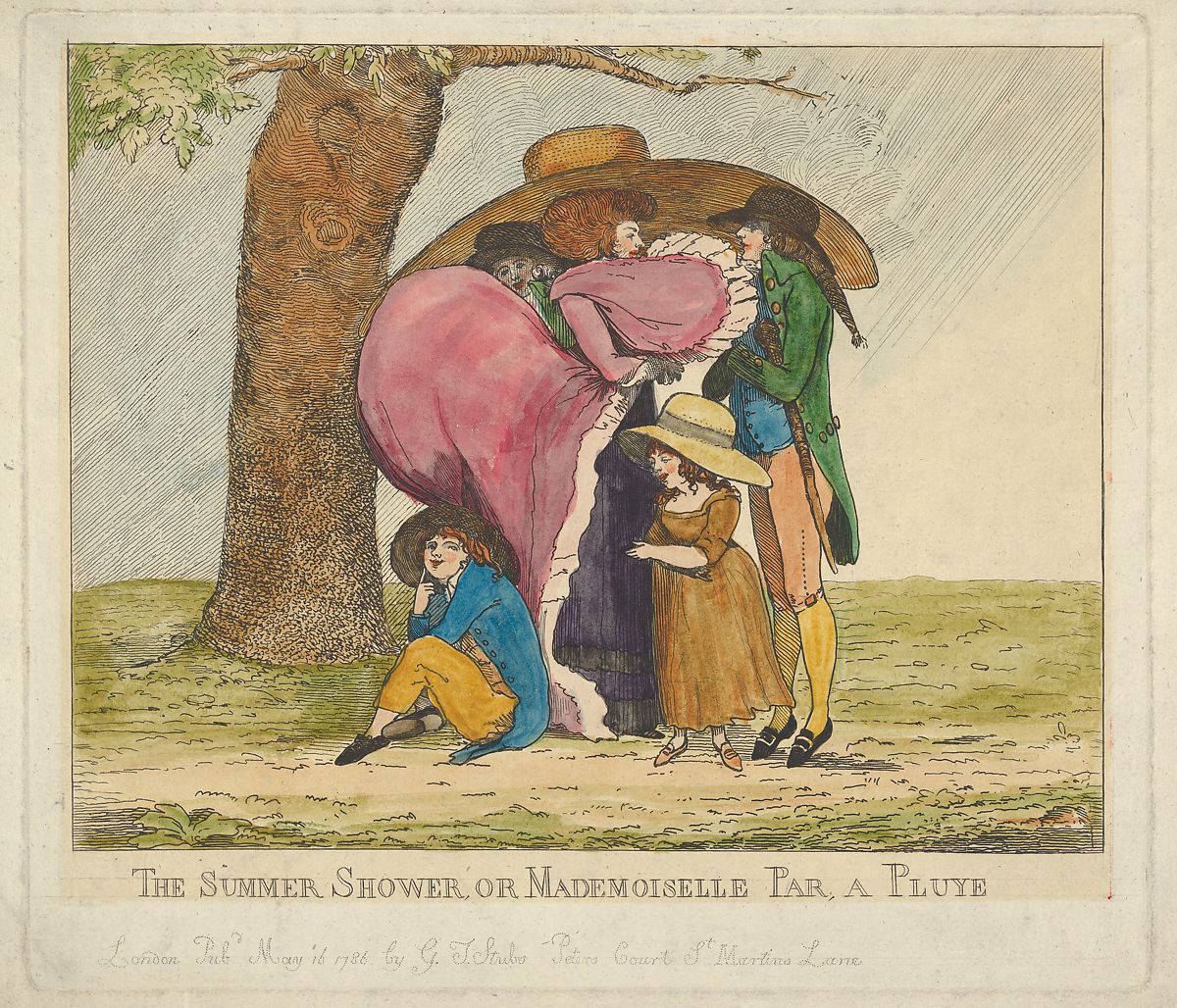

The main difference between the female silhouette of the 1770s and that of the 1780s was the latter's rounder shape that was achieved with understructure, accessories, in detail, the fichu, and changes in hairstyles (Figs. 1, 5, vii, 13, 20). Although the corset (now often half-boned) was withal essential in the creation of the stylish body, the various two-slice gowns referred to above would more often than not have been worn with a cork-filled crescent pad, known in U.k. as a "false rump" or "stale bum" and in French republic as a "cul de Paris" (Cunnington 336) (Figs. 28, 29). If not tied securely around the waist, the tapes might come loose, equally seems to have occurred in at least i instance every bit reported past Boondocks and State Magazine in 1785:

"Lost: a Lady's Rump in fine preservation, coming from the City Ball." (Cunnington/336)

The admiring hubby at Ranelagh noted that although his wife was unencumbered by stays nether her white muslin chemise, allowing for the "advantageous" display of "her piece of cake shape," her long ringlets "rested upon the unnatural protuberance which every fashionable female person at present chuses to affix to that part of her person," as seen in the portrait of Marie Anne Lavoisier (Fig. 16) (quoted in Cunnington/History of Underclothes 92).

To balance this posterior rotundity, women wore big white cotton, linen, or gauze fichus loosely folded and crossed over the bosom, sometimes with the ends tied effectually the dorsum of the waist, creating a pouter-pigeon effect (Figs. ane, 5, 8, xviii). In 1786, Sophie de la Roche commented on the "get-up of four ladies, who entered a box during the 3rd play."

Their "wonderfully fantastic caps and hats perched on their heads" drew "loud derision" from the audition, and "their neckerchiefs were puffed up and then high that their noses were scarce visible, and their nosegays were like huge shrubs, large plenty to conceal a person." (quoted in Waugh/Women 125)

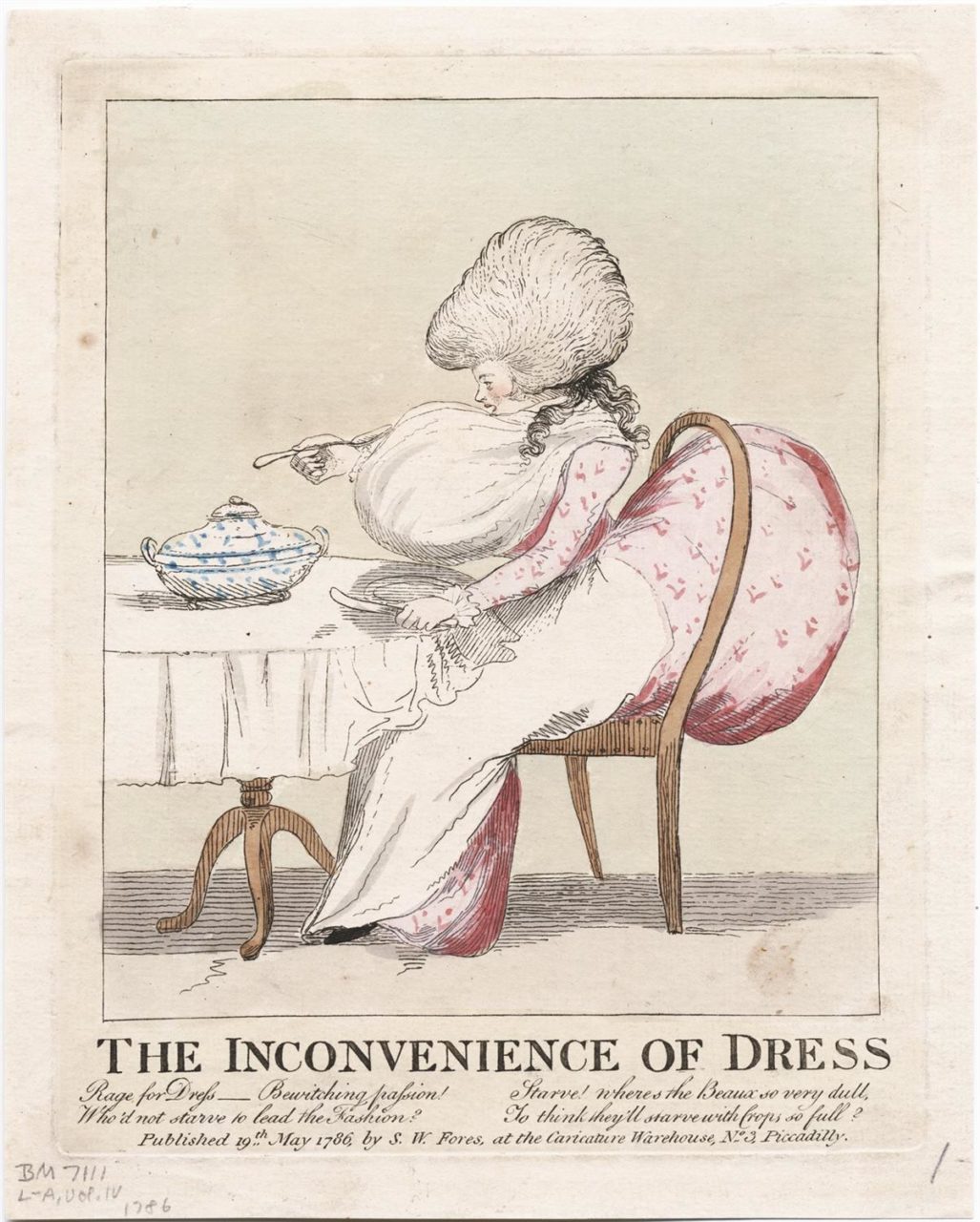

Large muffs, that were a betoken of mode for both immature women and men in the 1780s, further exaggerated this silhouette especially when held direct in front of the bosom (Fig. 30). Caricaturists relentlessly satirized the pros—depending on one's bespeak of view—and more often than not cons of these spherical female proportions (Figs. 31, 32).

Although sizable coiffures continued to exist fashionable in the 1780s, the verticality of the previous decade's hairstyles was replaced by an aureole-like shape that besides involved the use of imitation hair, powder, and pomatum (Figs. 5, 8, xiii, 16, 20). To accommodate these new coiffures that were more than conducive to headwear, milliners confected hats and bonnets of suitably big dimensions with expansive brims and crowns topped with improvident ribbons, plumage, and other ebullient decorations. The Galerie des Modes and Cabinet des Modes (and its subsequent versions) nautical chart the frequent changes in these all-important accessories that communicated the wearer's familiarity with the latest novelties that even the Cabinet's editor sometimes acknowledged varied merely slightly from what he had heralded as the most au courant style in the previous upshot (Figs. 4, 5, 8, nine, 10, 13, 17, 18, 20, xxx, 33). In his Tableau de Paris (1783), the social commentator and urban ethnographer Sebastien Mercier commented on the fleetingness of women's fashions—including headwear—that were out of date before he could put them to pen. The women of like shooting fish in a barrel virtue who patrolled the Palais-Royal—a favorite hunting ground—

"walk two by two to grab men'southward eyes dressed in the latest spoils of the milliner, mad modes too, some of them, which concluding a day or two, and so are forgotten fifty-fifty by their own inventors. The names of these fashions would make full a dictionary of several volumes page; nevertheless, we accept no such useful guide as yet…." (Mercier 207)

In France, the straw hat, associated with English country life, was sartorial shorthand for fashion's analogousness with the pastoral (Figs. ane,vii, 15, 17, 18). The marchande de modes (Fig. 33), or milliner, reigned supreme in the terminal decades of the eighteenth century. The relative simplicity of women's main garments in both shape and textile during this menses was about obscured past their accompanying accessories and trimmings (Fig. 34) including "feathers, ribbons, tassels, lace, bogus flowers and other ornaments" that were provided past these fashion merchants and often considerably pricier than the gowns themselves (Chrisman-Campbell 52).

Fig. 27 - Designer unknown (French). Robe à 50'anglaise, ca. 1784-1787. Cotton, metallic, silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art, 1991.204a, b. Purchase, Isabel Shults Fund and Irene Lewisohn Heritance, 1991. Source: The Met

Fig. 28 - Designer unknown (British). Stays, 1780-1789. Linen, linen thread, ribbon, chamois and whalebone. London: Victoria and Albert Museunm, T.172-1914. Mrs Strachan. Source: V&A

Fig. 29 - R. Rushworth (British, active 1785–86). The Bum Shop, July 11th, 1785. Mitt colored etching; 31 x 44 cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1970.541.12. The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund and Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, by Commutation, 1970. Source: The Met

Fig. xxx - Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun (French, 1755-1842). Madame Molé-Reymond, from the Italian Comedy (1759-1833), ca. 1786. Oil on wood. Paris: The Louvre, MI 694. Reymond, Maurice Gabrielle Hélène Françoise (model'south daughter). Source: Louvre

Fig. 31 - Creative person unknown (British). The Summer Shower, or Mademoiselle Par, a Pluye, May 16th, 1786. Etching, manus colored; 23.8 x 27.3 cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1971.564.190. The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1971. Source: The Met

Fig. 32 - George Townley Stubbs (British, c. 1756-1815). The Inconvenience of dress, 1786. Hand-coloured etching. London: The British Museum, 1851,0901.298. Donated by: William Smith, the printseller. Source: Yale University Library

Fig. 33 - Creative person unknown (French). Les Belles marchandes de Paris, 1784. Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France. Source: BNF

As apparel historian Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell notes,

"marchandes de modes were convenient (if problematic) symbols of class, consumption, and sexuality. Past displaying themselves to public view in magasins de modes (fashion shops) and in the streets, [they] provoked controversy and curiosity" and these women "came to personify fashion itself, with all its glamour and foibles." (Chrisman-Campbell 53-54)

The virtually renowned marchande de modes in Paris was Rose Bertin, whose shop, "Au Chiliad Mogol," was on the exclusive Rue St. Honoré. Bertin'due south services to the manner-obsessed Marie Antoinette secured her reputation among an affluent international clientele who were willing—when they settled their bills, sometimes on an annual basis—to pay her exorbitant prices and made her the target of critics, who decried her undue influence over the queen and what was perceived equally her familiarity with—and even insolence towards—her high-ranking customers.

In add-on to dressmakers who were instrumental in the invention and dissemination of new styles, the burgeoning fashion press on both sides of the Channel kept women in urban centers every bit well every bit rural areas increasingly up to date with changes in style. In France, the Cabinet des Modes, edited by Jean Antoine Brun, appeared in October 1785, slightly overlapping with the Galerie des Modes (1778-1787). Published every xv days until October 1786, "it provided its subscribers with three color engravings and eight pages of text on the latest fashions" (Jones 181). Over the next three years until December 1789, the journal, renamed Magasin des Modes nouvelles françaises et anglaises was edited by Louis Edme Billardon de Sauvigny, and, in February 1790—simply six months after the autumn of the Bastille—Brun took the captain once over again and inverse the title to Periodical de la mode et du goût (Jones 181). The Cabinet des Modes (and its subsequent iterations) "provided a detailed view of how the 'fashion organization' worked…and explicit commentary on the nature of la way…[also as] regularly discussing its own part in the civilisation of manner" (Jones 181). In her examination of this journal, historian Jennifer Jones argues that "the fashion press played a crucial office in disseminating a new vision of the relationship between women, fashion, and commercial culture" and "relegating" fashion and its associations with frivolity and ephemerality to "the realm of gustation rather than the serious realm of fine art and politics" (Jones 180).

Fig. 34 - Michel Garnier (French, human action. 1793-1814). A Fashionably Dressed Young Adult female in the Arcade of the Palais-Royal, 1787. Source: Pinterest

Significantly, although publications similar the Galerie des Modes and the Cabinet des Modes depict upper-form men and women, they simultaneously reflect the growing consumption of fashion that encompassed the middle and working classes and marking a shift in the locus of trendsetting styles from the court to the city of Paris (Jones 182).

In England, Barbara Johnson'due south album attests to the popularity of what were known as Pocket Books that were "issued especially for women [and] appeared in quantity…during the 2nd half of the eighteenth century" (Rothstein 36). These small books included "pages ruled for engagements calendar month by month" as well as a diversity of data such every bit "hackney carriage rates; new taxes… new country dances, songs, cookery recipes…[and] i or two way engravings" (Rothstein 36). Beginning in 1754, Johnson affixed engravings from "16 named publications, as well as many unidentified plates" to the pages with her cloth swatches (Rothstein 36). From her home in Buckinghamshire, Johnson had access to The Ladies Complete Pocket Volume (first published in 1758 and one of her favorites, judging by the 15 times that identified engravings appear in the anthology between 1770 and 1825); The English Ladies Pocket Companion or Useful Memorandum Book; Carnan's Ladies Complete Pocket Volume; The Ladies New Memorandum Book among several others (Rothstein 36-37) (Figs. 24, 25). In add-on to Pocket Books, more mode-focused magazines were also available such every bit The Lady's Magazine (the quaternary publication with that name) that began in 1770 (Rothstein forty).

Fashion Icon: LOUISE CONTAT (1760-1813), French actress

Fig. 1 - Jean-Baptiste Greuze (French, 1725–1805). Louise Contat, ca. 1786. Pastel. Source: Wiki

Fig. 2 - Jacques Philippe Joseph de Saint Quentin (French, b. 1748). 'The mad day, or the marriage of Figaro', ca. 1784. Etching; 16.4 x ten cm. New York: The Met, 2012.136.58.2. Phyllis Massar, 2011. Source: The Met

In 1784, Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais' controversial play and succès fou, The Marriage of Figaro, ensured the reputation of Louise Contat as a gifted extra and style trendsetter (Fig. 1). Although leading actresses and ballet dancers had set new styles throughout the century, the establishment of a regular manner press beginning in the 1770s added to their visibility and renown and reinforced the mutually beneficial human relationship betwixt fashion and the theatre. Beaumarchais himself recognized this relationship in the preface to the published edition of Figaro:

"Because characters in a play show themselves to accept depression morals, must we banish them from the stage? What should we seek at the theatre? Foibles and absurdities? That's well worth the problem of writing about! They are like our fashions; nosotros can't right them, then we change them." (quoted in Chrisman-Campbell 215)

Born in Paris in 1760, Louise Contat debuted at the Comédie-Française at age sixteen in 1776 in the role of Atalide in Jean Racine's 1672 play, Bajazet. In response to the mixed reviews that acknowledged her "charming figure," only plant her talent somewhat lacking, Contat undertook further dramatic studies and lessons in elocution. Following subsequent performances in Zaïre and Britannicus, she was fabricated a sociétaire of the Comédie Française in 1777—a decision that may also take been prompted by her liaison with a high-ranking admirer, with whom she had two children. Dubbed the "Vénus aux belles fesses" by the underground press, Contat next attracted the attention of Charles Philippe, comte d'Artois, younger brother of Louis Xvi, and in December 1780, she gave birth to their son. As mistress to a fellow member of the royal family, Contat's career benefited and she was offered enviable roles. Her beauty and vivacity were particularly well suited to ingénue parts and her appearances in Le Vieux Garçon by Paul-Ulric Dubuisson, Les Courtisanes by Palissot, and La Coquette corrigée in the early on 1780s brought her acclaim. Following her breakout office in The Spousal relationship of Figaro, Contat enjoyed many further theatrical triumphs playing lovers, coquettes, and young mothers. In 1785, the extra was awarded a pension from the royal treasury, and she remained loyal to the Bourbon family after the outbreak of the Revolution in July 1789.

Although she was a confirmed royalist, Contat was protected past leading members of the Revolutionary authorities after the fall of the monarchy in August 1792; withal, she was imprisoned in 1793, sentenced to death, and narrowly escaped the guillotine. In 1799, she returned to the Comédie-Française, where she reclaimed her pre-Revolutionary successes, performing until her retirement in 1809. Her salon, that she established during the Directoire (1795-99), drew guests from the highest echelons of Ancien Regime society. Contat died of cancer in 1813 and is buried in Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris.

Although Beaumarchais's play The Hairdresser of Seville (1775), the first in his trilogy that introduced the scheming, upstart character of Figaro, was well received, it was the 2d, The Marriage of Figaro, that became a awareness (Figs. 2, 3, four). Following its wildly successful first performance at the Comédie-Française in forepart of a packed house filled with members of the aristocracy, the play spawned a host of feminine fashions, named for both male and female characters including Figaro, Suzanne (maidservant to Countess Almaviva, the object of Count Almaviva's desire, and Figaro's wife-to-exist), and Chérubin (a male page), that filled the pages of the Galerie des Modes (1778–87) and the Cabinet des Modes (1785–86). A 1785 plate (Fig. v) from the quondam presents a "young and elegant Suzanne" holding a letter of the alphabet to "her love Figaro" dressed in a muslin "caraco" (jacket bodice) and skirt—typical attire for a lady'due south maid that "crossed over into style in the 1780s," largely due to Figaro (Chrisman-Campbell 212). In the same year, a "bright nymph" of the Palais-Royal, with a coiffure "à la Suzanne" and a juste (another name for a hip-length jacket) "à la Figaro," offers "to the optics of the public the charms of her face and the elegance of her shape" that concenter high praise, while another "nymph" walking in a public promenade with hopes of meeting an admirer wears a lid "à la Chérubin" (Fig. half-dozen). The Cabinet des Modes illustrated a (presumably respectable) woman in formal wearing apparel accessorized with a gauze bonnet "à la Figaro" (Fig. 7).

In its outcome of November twenty, 1786, the Magasin des Modes nouvelles referred to bonnets "à la Turque" and "à la Randan" (known by some as "à la Bayard") that owed their origin to the "exquisite gustatory modality of the famous Actress who played the function of Madame de Randan in Les Amours de Bayard, a new comedy by M. Monvel". Lest its readers were unaware of the identity of this "famous Extra," the editor added a note clarifying that she was "Mademoiselle CONTAT, who had already created hats à la Suzanne, à la Figaro, &c".

Fig. 3 - J. Coutellier (French, 1776-1789). Louise Contat in the Role of Suzanne in Pierre Beaumarchais's "Le Mariage de Figaro" (The Marriage of Figaro), ca. 1784. Engraving. New York: BGC Visual Media Resources Collection, 215945. Source: Alamy

Fig. 4 - J. Coutellier (French, 1776-1789). Jeanne-Adelaide Olivier in the Function of Chérubin in Pierre Beaumarchais's "Le Mariage de Figaro", ca. 1784. Source: Alamy

![]()

Fig. 5 - Nicolas Dupin (French). Folio from Gallerie des Modes, ca. 1778-1785. Engraving; 23 x sixteen cm. Paris: National Library of French republic. Source: BnF Gallica

![]()

Fig. six - Nicolas Dupin (French). Page from Gallerie des Modes, ca. 1778-1785. Engraving; 23 ten 16 cm. Paris: National Library of France. Source: BnF Gallica

Fig. 7 - Artist unknown (French). Bonnet de gaze soufflée, à la Figaro, surmonté de deux plumes blanches soutenues par une guirland de fleurs, Dec 1st, 1785. Engraving. Tokyo: Bunka Gakuen University Library, SB00002310. Source: Bunka Gakuen

In 1787, the Galerie des Modes depicted a immature woman in a redingote with steel buttons and a wide-brimmed hat with striped ribbons and a large standing frill dubbed "à la Contat" after the extra herself (see Chrisman-Campbell 215). In attempting to explain the success of Contat's hats, the Magasin des Modes nouvelles suggested at least ane reason why women desired to re-create actress fashions:

"Most of our ladies who accept adopted these hairstyles have convinced themselves that they will make conquests as hitting [as Mlle Contat'southward characters had made on stage and Mlle Contat had made off stage], or at least volition have the same seductive aura as Mademoiselle Contat." (quoted in Jones 189-190)

However, the periodical cautioned its readers confronting too closely emulating actresses and to limit their toilettes to the private rather the public sphere: "One must accept the nigh small, decent, naïve, soft and circumspect tone: the to the lowest degree flake of freedom, the slightest arrayal, will give one the wait of a prostitute" (quoted in Jones 190). In spite of the appreciation of their talents, their enormous popularity, and their best-selling roles every bit fashion leaders, actresses were equated with the "nymphs" who sold their bodies—presumably to the highest bidder—until the turn of the twentieth century.

Menswear

Fig. 1 - Thomas Gainsborough (English, c. 1727-1788). George Drummond, ca. 1780s. Oil on sheet; 233 x w 151 cm. Oxford: The Ashmolean Museum of Fine art and Archæology, WA1955.62. Source: Art Britain

Fig. 2 - Designer unknown (English or French). Riding glaze, ca. 1780s. Wool plain weave, full finish, with metal-thread embroidery. Los Angeles: Los Angeles Canton Museum of Art, M.2007.211.46. Source: LACMA

Asouth in the 1770s, the chief influence of fashionable menswear came from England. The trend towards simplicity and informality of the English state gentleman's attire that took agree in that decade became more pronounced in the 1780s and was emulated by fashionable immature men in France and elsewhere on the Continent (Figs. 1, 2). In the French capital, frock coats, jockey hats, and riding boots were expressions of the Anglomania that swept the country at this fourth dimension, as indicated past the renamed Magasins des Modes Nouvelles françaises et anglaises. Sebastien Mercier deplored this obsession with all things English:

"Just now English clothing is all the rage. Rich human being'south son, sprig of nobility, counter-jumper shop clerk—you see them dressed all alike in the long coat, cut shut, thick stockings, puffed stock; with gloves, hats on their heads and a riding switch in their easily. Not one of the gentlemen thus attired, however, has ever crossed the Channel or can speak one word of English… [East]nglish coats, with their triple capes, envelop our young exquisites. Pocket-sized boys wear their pilus cutting round, uncurled and without powder…" (Mercier 148-149)

Although the writer conceded that "the apparel is neat, and implies a well-nigh exact cleanliness of person," he nonetheless implored his "young friend[s]" to "keep your national frippery" and to

"dress French once more, article of clothing your embroidered waistcoats, your laced coats; pulverization your hair… keep your chapeau under your arm, and wear your 2 watches, with concomitant fobs, both at one time. Character is something more than apparel." (Mercier 148)

Across these imitations of English apparel that he institute distasteful, Mercier besides noted other objectionable imports from France'southward longstanding rival:

"Shopkeepers hang out signs—'English Spoken Hither.' The lemonade-sellers even have succumbed to the lure of punch, and write the word on their windows… [T]he racecourse at Vincennes is copied from that at Newmarket. … [A]ll these modes and drinks and customs would accept been rejected, and with disdain, by the Parisians of thirty years ago" (Mercier 149).

Co-ordinate to Mercier, the equine fascination among his male compatriots (that would persist into the nineteenth century) resulted in the abandonment their mistresses:

"Young men are mad about horses, and for some time take ignored the ladies of the Opera—the courtisanes resent this treatment; the young men have them out less and their horses more; until the evening, all dress like grooms; they look awkward in dress clothes." (quoted in Waugh/Men 108)

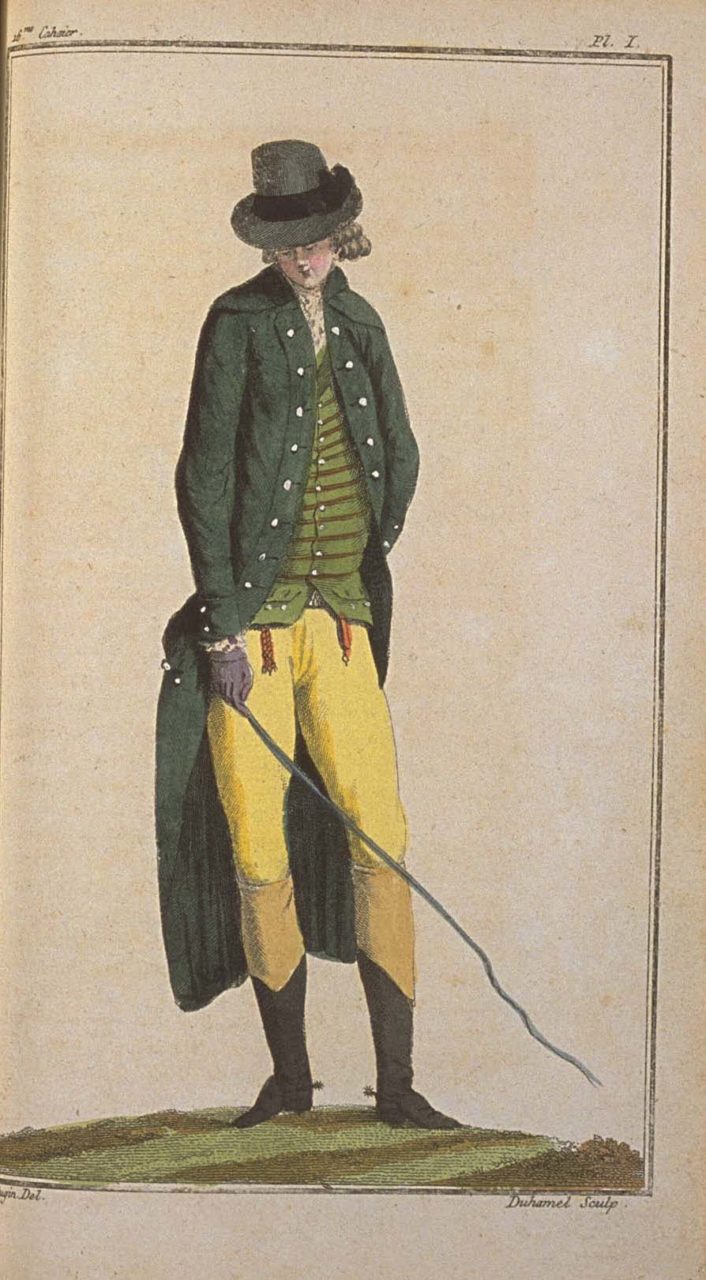

A dashing speculator striding in the Palais Royal (Fig. iii)—seemingly having just dismounted—wears a total English ensemble comprising an umber-colored apron coat with an imbricated blueprint, straight-cut striped waistcoat, thigh-hugging buckskin breeches, a "Jockey" hat, striped stockings, riding boots, and spurs. In July 1786, the Magasin des Modes Nouvelles showed a young human being, set "to mount his equus caballus," in a "dragon-green" double-breasted glaze with mother-of-pearl buttons, a striped waistcoat, leather breeches, paired watch fobs, and "Bottes Anglaises" with silver spurs (Fig 4). Describing the sights and sounds of the Palais-Royal, Sebastien Mercier observed that

"you can hear [the immature men] coming from 1 finish of the place to the other, by the tinkle of chains for the two watches they habiliment." (Mercier 206)

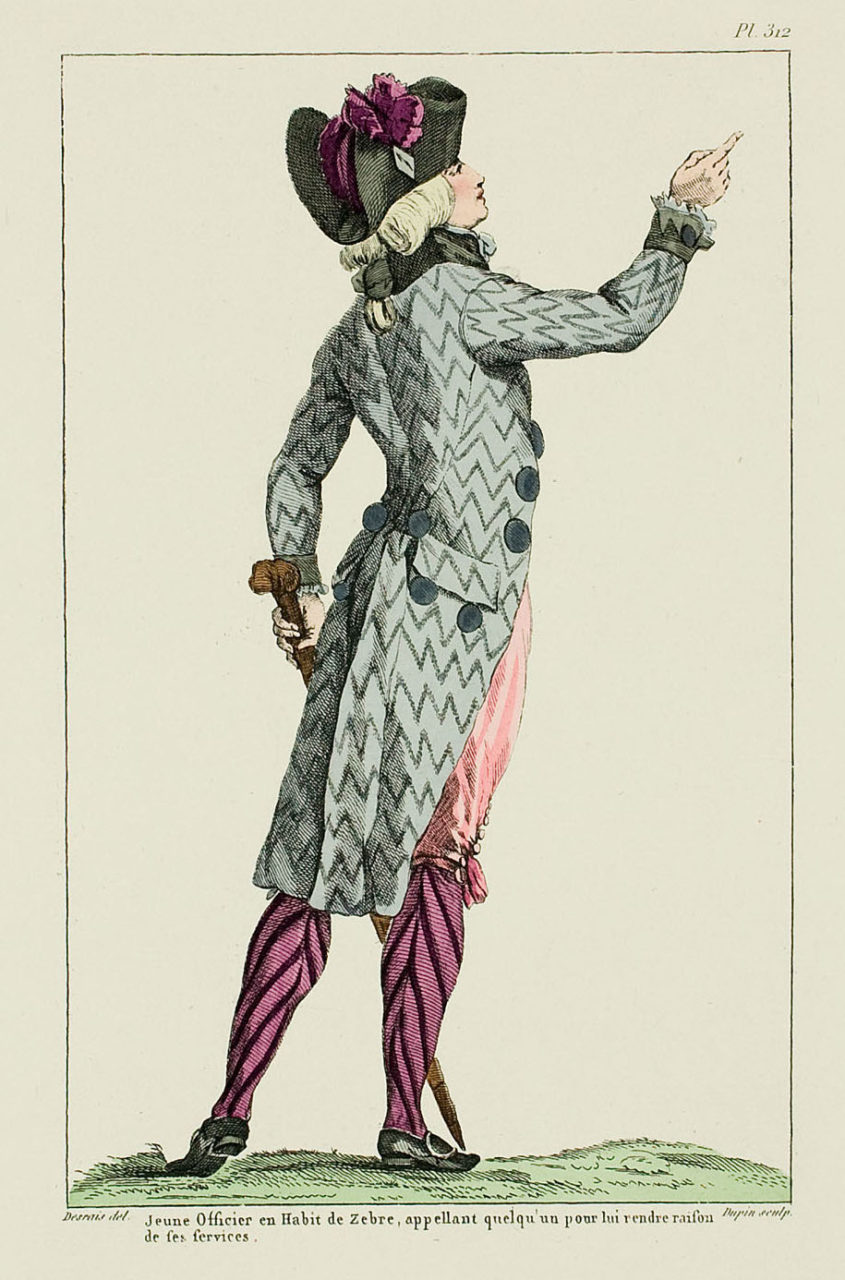

While young Frenchmen embraced the form of English language attire, they often preferred more than lively patterns and hues than the subdued, solid colors preferred by their counterparts across the Channel (Fig. 3). Throughout the 1780s, stripes decorated coats, waistcoats, and stockings (Fig. 5). In 1787, Mercier attributed this fashion to the zebra in the rex'southward menagerie:

"coats and waistcoats imitate the handsome creature's markings as closely as they can. Men of all ages have gone into stripes from head to human foot, fifty-fifty to their stockings." (quoted in Ribeiro/Dress in Eighteenth Century Europe 208).

Although the waistcoat had been a focal point of the conform throughout the century, information technology provided additional eye-catching interest in the 1780s and 1790s, especially when worn with a apparently glaze and/or breeches; like women's hats, these garments signified the wearer'southward individual sense of taste and attending to the latest trends that were oft inspired by topical events including theatrical productions (such as Henry Purcell's opera, Dido and Aeneas) and literature too as exotic animals (Figs. 6-eight).

Fig. iii - Artist unknown (French). Stock Market Speculator in Morning Apparel and Chapeau Jokei, Volume IV, plate 282, 1787. Engraving. New York: BGC Visual Media Resources Collection, 203592. Source: Dikats

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown (French). English Boots and Striped Waistcoat, ca. 1780s. Engraving. Tokyo: Bunka Gakuen Academy Library, SB00002310. Source: Bunka Gakuen

Fig. 5 - Nicolas Dupin (French). Galerie des modes et costumes français, ca. 1778-1787. Engraving. Tokyo: Bunka Gakuen Academy Library, BB00114340. Source: Bunka Gakuen

Fig. six - Designer unknown (French). Waistcoat, ca. 1780s. Silk, linen. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 256-1880. Source: Five&A

Fig. seven - Designer unknown (French). Embroidered Waistcoat, ca. 1785-1795. Silk, embroidery. New York: Cooper Hewitt, 1962-54-47. Bequest of Richard Cranch Greenleaf in retention of his mother, Adeline Emma Greenleaf. Source: Cooper Hewitt

Fig. 8 - Designer unknown (French). Waistcoat, ca. 1780-1789. Silk, linen, embroidery. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.49-1948. Source: V&A

Fig. 9 - Joseph Wright of Derby (English, c. 1734-1797). Sir Brooke Boothby, 1781. Oil on sheet. London: Tate Museum, N04132. Bequeathed by Miss Agnes Ann All-time 1925. Source: Tate

Fig. 10 - Joseph Boze (French, 1745-1826). Louis-Stanislas-Xavier, comte de Provence (afterwards Male monarch Louis XVIII, King of France) (1755-1824), 1786. Oil on canvas; 194 ten 138 cm. Buckinghamshire: Hartwell Business firm, 1548061. Source: National Trust

Fig. 11 - Designer unknown (French). Adapt, ca. 1780-1785. Silk, velvet, foil, sequins. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1000.2007.211.950a-c. Source: LACMA

The contrast between men's informal day and formal evening wearable is evident in Joseph Wright of Derby's portrait of Sir Brooke Boothby (Fig. 9) and Joseph Boze's depiction of the Comte de Provence, younger brother of Louis XVI and hereafter Louis XVIII (Fig. x). Wearing apparel historian Aileen Ribeiro notes that while Boothby's

"portrait has been seen, both in pose and in apparel, every bit influenced by late Elizabethan and Jacobean melancholy… the costume is certainly not indicative of a melancholic déshabillé, simply a definite statement of high fashion." (Fine art of Dress 48)

Carefully reclining on the ground in a wooded landscape and property a copy of Rousseau. Juge de Rousseau, Boothby wears a three-piece matching suit of soft brown wool consisting of a slim-fitting double-breasted frock with turned-down neckband and wide lapels and tight sleeves that have been unbuttoned at the wrist to afford greater ease of movement, a double-breasted waistcoat, and close-fitting breeches secured with buttons above the outer genu, white silk stockings, and black low-heeled buckled shoes (Fig. ix). The neutral colour and plainness of his adjust sets off the whiteness of his equally evidently white linen shirt and cravat, tied in a bow. Ribeiro notes that "Oxford Street in London was famous for its shops selling a wide range of cottons and linens, and was particularly admired past strange visitors in the 1780s" (Art of Dress 48). Prepare at an angle on Boothby'south unpowdered pilus is a chapeau with a circular brim and a round crown known every bit a "wide-awake"; by the 1780s, this style "largely replaced the cocked iii-corner lid which became the preserve of the conservative and the quondam-fashioned" (Ribeiro/Fine art of Dress 49).

At the other end of the spectrum, the Comte de Provence, seated on a golden chair upholstered in red damask, wears a richly embroidered habit à la française with coat and breeches of pale blueish silk glittering with gold spangles and a coordinating white silk waistcoat, covered in embroidery (Fig. x). A former page to Louis Sixteen described the king'south formal clothes of the 1780s that closely corresponds to Provence's conform:

"on Sundays and ceremonial occasions his suits were of very beautiful materials, embroidered in silks and paillettes. Often, as was the fashion and so, the velvet coat was entirely covered with little spangles, which made information technology very dazzling." (quoted in Waugh/Men 107)

The belatedly-eighteen-century formal suit was distinguished from the apron non merely by its rich materials, but by its standing collar that emerged in the 1760s and grew in meridian through the stop of the century, single-breasted closure, and the inverted-Five shape of the single-breasted waistcoat skirts. While the placement of the embroidery on Provence's coat forth the eye front edges, cuffs and pocket flaps is consequent with that seen in earlier decades, the delicate floral sprays and bowknot motifs are typical of the last quarter of the century and reflect an overall alter in artful from the heavier, lush ornamentation that previously characterized this type of ornament (Fig. 11). Throughout the century, clients purchased uncut panels embroidered with all the pieces of the conform that were later made upwards past a tailor for the individual wearer (Fig. 12).

Unlike Boothby'due south evidently linen, Provence'due south shirt frill and cuffs are of floral needle lace (probably French) and, although his buckled shoes are low-heeled like the Englishman'south, their cerise color had been associated with the French court since the reign of Louis XIV. (Fig. 10). Similarly, Provence's powdered and curled wig with its queue encased in a black silk bag was strictly relegated to court wear by the last decades of the century. And, like the page's description of his brother the male monarch, the count wears a jeweled epaulet and the bluish ribbon with the Order of the Holy Spirit that, along with aristocratic titles, would be abolished in the early years of the Revolution (Waugh/Men 107).

At the coming together of the Estates Full general in May 1789, called for the beginning time since 1614 past Louis XVI in 1788, the sartorial display of wealth and status that distinguished the aristocratic members of the Showtime Estate became a lightning rod for the country's centuries-long social, political, and economic inequities. Rejecting both his class and its prerogative to article of clothing silks and lace, the Comte de Mirabeau joined the Third Estate and donned the prescribed black wool adapt and manifestly linen, in which he was depicted by Joseph Boze (Fig. 13)—the aforementioned artist who had painted the Comte de Provence (Fig. x) iii years earlier.

PALAIS-Majestic

Many Galerie des Modes plates locate the fashionable figures in the Palais-Royal (Figs. 3, fourteen). Following its refurbishment in this decade by the hugely wealthy anglophile Philippe d'Orléans, duc de Chartres, cousin of Louis Sixteen, whose family unit had lived in the Palais-Imperial since the second one-half of the seventeenth century, it became the epicenter of Parisian highlife frequented by aristocracy society, conservative men and women, dodgy speculators, ladies of the night, and tourists from all over Europe and beyond (Fig. 34 in womenswear). The elegant, arcaded galleries were filled with shops, auction galleries, concert rooms, gambling clubs, Turkish baths, cafés, and brothels (Fig. 15). John Villiers, an English visitor in 1788, found the shops:

"the best in Paris, which produce a prodigious rent to the Knuckles. Every affair that is rich, brilliant, and cute, is exposed to sale, at these different boutiques; the splendour of which, together with the pleasantness of the walks, and the croud [sic] of well-dressed company makes this place truly enchanting and delightful." (quoted in Chrisman-Campbell 57)

Clothing shops—and the possibility to transform oneself—were prominent in what was derisively referred to as "le Palais marchand:"

"Go to the Palais-Royal dressed as an American barbarous, and in the infinite of half an hour, you volition exist dressed in the most perfect manner." (quoted in Chrisman-Campbell 57-58)

Fig. 12 - Designer unknown (French). Embroidered panels for a man'due south suit, 1780s. Silk embroidery on woven silk, satin stitch; stalk stitch, knots and silk net; 114.ix × 56.5 cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1982.290a–eastward. Purchase, Irene Lewisohn and Alice L. Crowley Bequests, 1982. Source: The Met

Fig. 13 - Joseph Boze (French, 1745-1826). Count of Mirabeau (1749-1791), 1789. Oil on canvas; 214 10 116 cm. New York: BGC Visual Media Resources Collection, 207630. Source: AKG

Fig. 14 - Nicolas Dupin (French). Galerie des Modes, 48e Cahier, 5e Figure, pl. 222, ca. 1785. Source: Mimic of Modes

For the more skeptical Paris-dweller, Sebastien Mercier, this "Pandora'south Box," characterized by sensory overload, was filled with seductive attractions that could lead to ruin (Mercier 205). Declaring it "unique; nothing in London, Amsterdam, Vienna, Madrid tin compare with information technology. A man might be imprisoned within its precincts for a year or two and never miss his liberty…," he also warned of the "vices [that] hold sway there" and the venality of the "prostitutes [and] the stock-commutation dealers [who] run across hither 3 times a day; coin is their one topic, and the prostitution of the State…" (Mercier 202, 205).

Although "prices [were] triple, quadruple the prices anywhere else," the Palais-Royal was never without those who came and paid, "specially the foreigners [like Villiers], who love having everything the center of human tin desire assembled in ane place, under one roof, for their pleasure" (Mercier 206).

On July 12, 1789, every bit the political situation in French republic (and Paris, especially) became more unstable, Camille Desmoulins, a young lawyer from Picardy, made an impassioned speech communication to the oversupply gathered in the gardens of the Palais Royal, exhorting his fellow citizens to take upwards artillery. Ii days later, the Bastille, the hated symbol of absolute monarchy and tyranny, was stormed by an angry mob and, over the side by side several months, completely destroyed.

Fig. xv - Philibert Louis Debucourt (French, 1755-1832). The Palais Regal Gallery'due south Walk, 1787. Color aquatint on paper. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1924.1344. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Potter Palmer, Jr.. Source: AIC

L eading into the eighteenth century, new philosophies emerging from the Age of Enlightenment were changing attitudes most childhood (Nunn 98). For example, in his 1693 publication, Some Thoughts Concerning Educational activity, John Locke challenged long-held beliefs nearly all-time practices for child-rearing. A slightly later child evolution theorist was Jean Jacques Rousseau. Locke and Rousseau both put forrard general principles well-nigh children'south wearing apparel. However, information technology was not until the 1760s that their ideas were conspicuously reflected in children'due south vesture (Paoletti).

Locke and Rousseau advocated that young children receive more regular hygiene. They also believed that dressing children in many layers of heavy fabrics was bad for their health. For those reasons, linen and cotton fabrics were preferred for babies and very young children because they were lightweight and easily washable (Paoletti).

Although the tradition was in decline, some infants may have been swaddled. Swaddling was a very long-held European tradition where an infant's limbs are immobilized in tight material wrappings (Callahan). The practice was losing popularity due to popular embrace of the opinions of Locke and Rousseau who opposed the exercise (Paoletti).

Babies were then dressed in "slips" or "long clothes" until they began to clamber (Fig. 1) (Callahan). These were ensembles with very long, full skirts that extended beyond the feet (Nunn 99). Babies also wore tight-fitting caps on their heads.

In one case a child was becoming mobile, they transitioned into "curt wearing apparel" (Callahan). Unlike long clothes, these ensembles ended at the ankles, allowing for greater freedom of movement (Callahan). Brusque gowns had back-opening bodices and sometimes "leading strings" attached at the back or tied under the arms (Magidson). Leading strings were streamers of textile used to protect young children from falling or wandering off ("Babyhood")

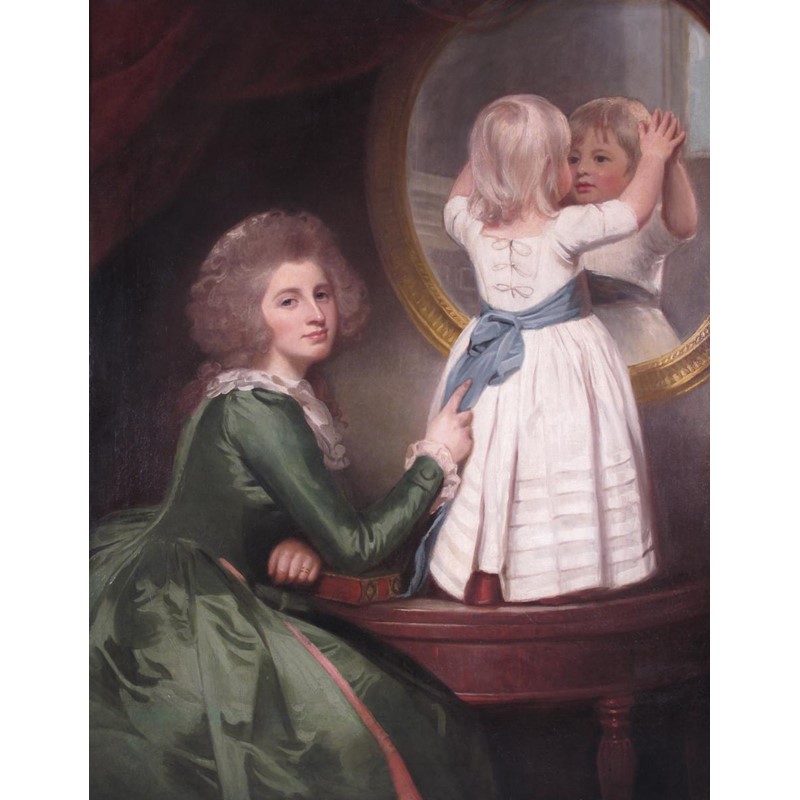

The style for short apparel in the 1780s had emerged in the 1760s: a white apron worn with a colored sash around the waist (Fig. 2). This fashion was worn by very immature children of both sexes. The nigh common sash colors were pink and blue, although they were not used to indicate gender. A colored underslip may have also been worn, which would show through the translucent white superlative textile (Paoletti). While this fashion originated with very small-scale children, it quickly became more pervasive. Past the 1780s, girls sometimes wore this style of wearing apparel even into their teenaged years (Nunn 99).

The 1780s saw a significant development in mode for young boys. Previously, young boys wore skirted gowns until they were "breeched" past age 7, and then wore adult menswear styles (Reinier). Nevertheless, new to the 1780s was a transitional type of ensemble for young boys called a "skeleton conform," which they would wear from approximately ages three to vii (Fig. 3) (Callahan). Skeleton suits

"consisted of ankle-length trousers buttoned onto a short jacket worn over a shirt with a broad collar edged in ruffles" (Callahan).

Older boys would so wear ensembles resembling adult menswear, although the fit was typically looser and more relaxed.

Fig. 1 - Thomas Gainsborough (English, 1727-1788). Detail from The Baillie Family unit, ca. 1784. Oil on canvas; 250.8 × 227.3 cm. London: Tate Museum, N00789. Bequeathed by Alexander Baillie 1868. Source: Tate

Fig. 2 - George Romney (English, 1734-1802). Lady Anne Barbara Russell and her son, ca. 1786-7. Oil on canvas; 144 x 113 cm. Private collection. Source: Wooley & Wallis

Fig. 3 - Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (Spanish, 1746-1828). Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zuñiga (1784–1792), 1787-88. Oil on canvass; 127 x 101.6 cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art, 49.seven.41. The Jules Bache Drove, 1949. Source: The Met

The Baillie Family, circa 1784, depicts James Baillie with his wife and four children (Fig. 4). Baillie's wife holds a baby wearing a long gown, which extends well past the infant's feet. The young boy wears a dark blue skeleton suit with a white collar, which is extremely similar to the one worn in The Oddie Children, circa 1789 (Fig. 5). However, one notable exception is the pink sash tied around his waist. The younger Baillie daughter wears a white gown with a bluish waist sash, and lifts her brim to reveal a dark blue underslip. Her ensemble is not unlike those worn past the Oddie girls. The older Baillie daughter wears a more mature style of gown, nevertheless she wears a pervasively fashionable waist sash similar her younger siblings.

Fig. iv - Thomas Gainsborough (English, 1727-1788). The Baillie Family, ca. 1784. Oil on sheet; 250.8 × 227.3 cm. London: Tate Museum, N00789. Ancestral past Alexander Baillie 1868. Source: Tate

Fig. v - William Beechey (English, 1753-1839). The Oddie Children, 1789. Oil on sheet; 182.9 10 182.half-dozen cm. Raleigh: North Carolina Museum of Fine art Foundation, 52.9.65. Purchased with funds from the Land of North Carolina. Source: Wikimedia Commons

REFERENCES:

- Cadet, Anne. Apparel in Eighteenth-Century England. London: B. T. Batsford, 1979. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1148934170

- Blum, Stella, ed. Eighteenth-Century French Fashion Plates in Full Color, 64 Engravings from the "Galerie des Modes, 1778-1787." New York: Dover, 1982. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1099092948

- Brédif, Josette. Classic Printed Textiles from French republic, 1760-1843: Toiles de Jouy. London: Thames and Hudson, 1989. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/851978139

- Callahan, Colleen R. "Children's Clothing." In The Berg Companion to Fashion, edited past Valerie Steele. Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. Accessed Baronial 08, 2020. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1223089692

- "Childhood." In European Renaissance and Reformation, 1350-1600, edited past Norman J. Wilson, 319-321. Vol. 1 of Globe Eras. Detroit, MI: Gale, 2001. Gale eBooks (accessed August seven, 2020).https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2653/apps/doc/CX3034600137/GVRL?u=fitsuny&sid=GVRL&xid=480f4328.

- Chrisman-Campbell, Kimberly. Fashion Victims: Dress at the Court of Louis Sixteen and Marie Antoinette. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2015. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/909036350

- Cullen, Oriole. "Eighteenth-Century European Dress." In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed September sixteen, 2016.http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/eudr/hd_eudr.htm

- Cunnington, C. Willett. Handbook of English Costume in the Eighteenth Century. London: Faber, 1972. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/397113

- _______, and Phillis Cunnington. The History of Underclothes. New York: Dover Publications, 1992. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/868279842

- "Introduction to 18th-Century Fashion." Victoria & Albert Museum. Accessed September 16, 2016.http://www.vam.air conditioning.uk/content/articles/i/introduction-to-18th-century-mode/

- James-Sarazin, Ariane, and Régis Lapasin, Gazette des Atours de Marie-Antoinette: Garde-robe des atours de la reine: Gazette pour l'année 1782. Réunion des musées nationaux – Athenaeum nationales, 2006. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/738549606

- Jones, Jennifer. Sexing La Way: Gender, Fashion and Commercial Civilization in Former Authorities France. Oxford and New York: Berg, 2004. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1201426327

- Le Coton et la Fashion: one thousand ans d'aventures: x novembre 2000-eleven mars 2001, Musée Galliera, musée de la style de la Ville de Paris. Paris: Somogy éditions d'art, 2000. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/698138631

- Magasins des Modes Nouvelles francaises et anglaises. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10461536s/f7.item

- Magidson, Phyllis. "Fashion." In Encyclopedia of Children and Babyhood: In History and Lodge, edited by Paula S. Fass, 344-348. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Macmillan Reference USA, 2004. Gale eBooks (accessed August 7, 2020).https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2653/apps/doc/CX3402800166/GVRL?u=fitsuny&sid=GVRL&xid=0084684d. http://world wide web.worldcat.org/oclc/961280814

- Nunn, Joan. Fashion in Costume 1200-2000. Bridgewater, NJ: Distributed by Paw Prints/Bakery & Taylor, 2008.http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/232125801

- Paoletti, Jo Barraclough. "Children and Adolescents in the U.s.a.." InBerg Encyclopedia of World Clothes and Fashion: The U.s. and Canada, edited by Phyllis M. Tortora, 208–219. Oxford: Bloomsbury Bookish, 2010. Accessed Baronial 28, 2020. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/744701921

- Popkin, Jeremy D., ed. Panorama of Paris. Selections from Le Tableau de Paris by Louis Sebastien Mercier, based on the translation by Helen Simpson. Academy Park: Pennsylvania Land Academy Press, 1999. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1101345838

- Pratt, Lucy, and Linda Woolley. Shoes. London: V & A Publications, 1999. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/880102437

- Reinier, Jacqueline S. "Breeching." In Encyclopedia of Children and Babyhood: In History and Society, edited by Paula Southward. Fass, 118. Vol. ane. New York, NY: Macmillan Reference USA, 2004. Gale eBooks (accessed Baronial 7, 2020). http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/961280814

- Ribeiro, Aileen. The Art of Dress: Manner in England and France from 1750 to 1820. New Haven: Yale University Printing, 1995. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/263551344

- _______. Dress in Eighteenth Century Europe. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/988795293

- Rothstein, Natalie. A Lady of Style: Barbara Johnson's Album of Styles and Fabrics. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1987. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/748992365

- _______. Silk Designs of the Eighteenth Century in the Collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.Boston: Little, Brown, 1990. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/438246692

- Waugh, Norah. The Cut of Men's Dress. New York: Theatre Arts Books, 1964. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/927414537

- _______. The Cut of Women'south Apparel, 1600-1930. New York: Theatre Arts Books, 1968. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1074444804

- Weber, Caroline. Queen of Manner: What Marie Antoinette Wore to the Revolution. New York: Picador/Henry Holt and Company, 2006. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1028433074

- Wroth, William Warwick. The London Pleasure Gardens of the Eighteenth Century. London & New York: Macmillan, 1896. http://world wide web.worldcat.org/oclc/975991037

0 Response to "English Fashion 1813 English Fashion 1750"

Post a Comment